Abstract

The fourth enzymatic reaction in the de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis, the oxidation of dihydroorotate to orotate, is catalyzed by dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH). Enzymes belonging to the DHODH Class II are membrane-bound proteins that use ubiquinones as their electron acceptors. We have designed this study to understand the interaction of an N-terminally truncated human DHODH (HsΔ29DHODH) and the DHODH from Escherichia coli (EcDHODH) with ubiquinone (Q10) in supported lipid membranes using neutron reflectometry (NR). NR has allowed us to determine in situ, under solution conditions, how the enzymes bind to lipid membranes and to unambiguously resolve the location of Q10. Q10 is exclusively located at the center of all of the lipid bilayers investigated, and upon binding, both of the DHODHs penetrate into the hydrophobic region of the outer lipid leaflet towards the Q10. We therefore show that the interaction between the soluble enzymes and the membrane-embedded Q10 is mediated by enzyme penetration. We can also show that EcDHODH binds more efficiently to the surface of simple bilayers consisting of 1-palmitoyl, 2-oleoyl phosphatidylcholine, and tetraoleoyl cardiolipin than HsΔ29DHODH, but does not penetrate into the lipids to the same degree. Our results also highlight the importance of Q10, as well as lipid composition, on enzyme binding.

1. Introduction

There are six enzymatic steps involved in the de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway, which is nearly universal to all organisms [1,2,3,4]. The end product of the pathway, uridine monophosphate, is the starting point for the delivery of deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) precursors for the synthesis of DNA, nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) precursors for RNA, as well as glycoconjugates, and many more metabolically important molecules. The fourth enzymatic reaction in this pathway, the oxidation of dihydroorotate to orotate, is catalyzed by the flavoenzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) [5,6,7].

DHODHs can be divided into two major families or classes, I and II, based on the sequence similarities, rather than convergent evolution of different ancestral proteins, with a further subdivision of Class I into sub-classes IA and IB [8,9]. This division correlates with the quaternary structure, subcellular location of the enzymes, as well as their preferences for electron acceptors. Members of Class I are cytosolic, with Class IA enzymes being homodimers and Class IB enzymes being heterotetrameric proteins composed of two different proteins. DHODH from Escherichia coli is regarded as the prototype of Class II DHODHs [8,10]. In contrast to Class I enzymes, Class II DHODHs are monomeric membrane-bound proteins that use ubiquinones as electron receptors.

Human DHODH (HsDHODH) is located on the outside of the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) and uses ubiquinone Q10 as an electron acceptor, which functionally connects its activity to the respiratory chain [11,12,13]. Literature suggests that HsDHODH is a stand-alone enzyme not associated with any respiratory supercomplexes [14]. HsDHODH is probably the most studied member of the Class II enzymes because it is a target for anti-inflammatory drugs, such as leflunomide (ARAVA®), approved for rheumatoid arthritis and its active metabolite, and teriflunomide (AUBAGIO®), approved for multiple sclerosis, both proposed to interact with the same region of the enzyme as ubiquinone [15]. It was also recently validated as a target for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [16], as its inhibition overcomes the myeloid cell differentiation blockade. Therefore, novel and old HsDHODH inhibitors are of interest for the treatment of hematological malignancies and innovative treatment options [17,18], and four compounds have entered clinical trials [19,20]. Furthermore, mutations in HsDHODH have been identified as the cause of Miller syndrome [21,22], a rare autosomal recessive disorder (OMIM %263750) resulting in numerous abnormalities of the head, face, and limbs. HsDHODH was also recently identified as the mitochondrial gatekeeper of cell death by ferroptosis because its deletion promotes ferroptosis [23].

HsDHODH inhibitors also exhibit antiviral activity against a range of different viruses, with their effect being attributed to the depletion of the nucleosides that are necessary for the replication of the viral genome. HsDHODH inhibition has therefore been proposed as a potential alternative intervention strategy in severe viral infections, e.g., caused by the Ebola virus [24,25] or respiratory RNA viruses, including the coronaviruses [26,27]. During the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, several HsDHODH inhibitors have been shown to inhibit the replication of SARS-CoV-2 (and other RNA viruses) in cell cultures [28,29,30]. It is therefore no wonder that approved anti-inflammatory HsDHODH inhibitors, as well as compounds in clinical trials for AML, are now also tested for their effects in COVID-19 patients [28,31,32]. The bacterial E. coli DHODH (EcDHODH) is peripherally associated with the cytosolic membrane [33] and uses ubiquinones as electron acceptors during aerobic growth, but must also be able to use alternative electron receptors (menaquinone, demethylmenaquinone) during anaerobic growth [34]. The structure and proposed orientations of HsDHODH in the IMM and EcDHODH at the cytosolic bacterial membrane are illustrated in Figure 1A, which also displays the proposed location of ubiquinone within the membrane. The N-terminus of HsDHODH contains a bipartite signal consisting of a mitochondrial signal (MS) and transmembrane domain (TM) that determines its import and correct insertion into the IMM [13]. The N-terminal segments of Class II DHODHs are connected to the catalytic domain via a microdomain containing two alpha-helices (α1, α2). In the E. coli enzyme, this microdomain is an N-terminal patch of two alpha-helices followed by a short 310-helix [9]. This microdomain is proposed to determine the interaction of DHODH with the membrane, and the binding of the electron acceptor ubiquinone. We will henceforth refer to this protein segment simply as the α1-α2 microdomain. In HsDHODH and in the DHODH from Rattus norvegicus, this part of the enzyme is an important target for the binding of clinically used DHODH inhibitors, such as the active metabolite of ARAVA® or atovaquone, and the former drug candidate brequinar [7,35,36]. In EcDHODH, the structural elements corresponding to the MS and TM are missing, as illustrated in Figure 1A.

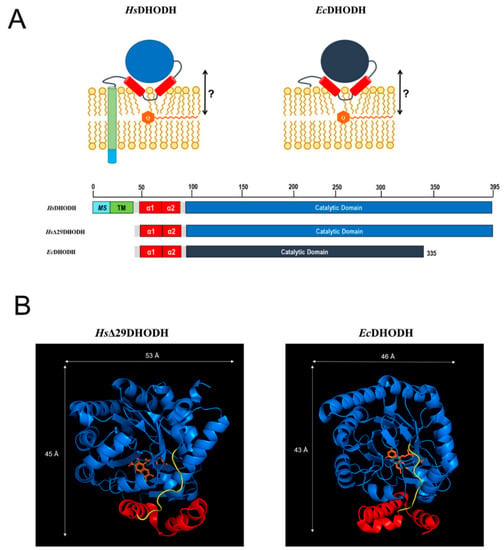

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of HsDHODH and EcDHODH in a lipid bilayer, and a comparative presentation of the proteins used in this study (HsΔ29DHODH, EcDHODH) with full-length HsDHODH. The N-terminus of HsDHODH contains a mitochondrial signal (MS) and a transmembrane segment (TM). These N-terminal parts of DHODH are connected to the catalytic domain via two alpha-helices (α1, α2) proposed to be critical for the interaction of HsDHODH with the IMM, and the electron acceptor ubiquinone Q10 (Q). The proposed location of Q10 in the IMM is also shown, with the question mark referring to the following question addressed in our study: how does the enzyme interact with its co-substrate Q10? The numbering indicates the amino acid count of the full-length HsDHODH sequence (Uniprot Q02127, PYRD_HUMAN), and indicates the shorter C-terminal length of EcDHODH (Uniprot P0A7E1, PYRD_ECOLI). (B) Crystal structures for N-terminal truncated HsDHODH (PDB ID: 2PRM) and EcDHODH (PDB ID: 1F76). The α1-α2 microdomain is shown in red, the catalytic domain is shown in blue, a potentially flexible loop connecting the α1-α2 microdomain to the core catalytic domain with the co-factor FMN (depicted in orange) is shown in yellow.

Many crystal structures of the soluble catalytic domain of HsDHODH in complex with inhibitors are currently available [7], but there are hardly any experimental structural data regarding the common feature of Class II DHODHs, the α1-α2 microdomain, or data concerning the enzyme in a membrane-bound state. To date, spectroscopic measurements indicate that the α1-α2 microdomain assumes a different conformation in detergent micelles and phospholipid vesicles [37], indicating that the nature of the membrane environment may play a role in the conformation adopted. Another interesting question is how the enzyme interacts with ubiquinone, which has been shown to be located in the hydrophobic center of lipid membranes [38], but it also needs to access the DHODH membrane-targeting α1-α2 microdomain as many DHODH inhibitors do [15]. Recently, it also has been proposed that inhibitor binding to DHODH is influenced by interactions with lipids in the IMM [39]. This is supported by previous findings showing differences in the inhibition of DHODH by brequinar, depending on whether the TM is present or not [35].

We therefore designed this study to understand the interaction of Class II DHODHs with membrane lipids and with the electron acceptor, ubiquinone. For our study, we chose the following two prominent members of Class II DHODHs: EcDHODH and HsDHODH. We performed a series of neutron reflectometry (NR) experiments in order to investigate the binding of both enzymes to a range of supported lipid bilayers with and without the co-substrate ubiquinone in order to determine what features of the membrane are important for the interaction with the enzymes and what role ubiquinone plays. These bilayers ranged from simple model bilayers that were prepared from synthetic lipids to complex lipid mixtures what were extracted from cell cultures. In order to focus on the proposed common feature of Class II DHODHs interaction with the membrane in this study, the α1-α2 microdomain, we compared the EcDHODH with an N-terminal truncated version of HsDHODH (HsΔ29DHODH), which lacks the MS and TM domains (Figure 1A). HsΔ29DHODH is comparable in enzymatic activity to the full-length HsDHODH that is found naturally in mitochondria and the is most used variant of HsDHODH studied throughout literature, also in interaction with lipids. Several reports of this, as well as comparisons of Class II DHODH with and without their N-terminal TM in vivo and in vitro studies have been published [13,35,40,41,42,43,44].

NR is a particularly well-suited technique for addressing these questions as it can determine the one-dimensional depth profile of single supported lipid membranes to 2–3 Å resolution, under solution conditions [45,46,47,48,49], and provide a low-resolution distribution profile of the embedded proteins using selective deuterium labeling of either the protein or the lipids. Recently developed methods allow the selective reconstitution of physiologically relevant membranes with a well-defined lipid composition [48]. NR is also well-suited for studying mechanisms and protein activity in situ [50,51,52], due to the flow-cell geometry of the samples. Additionally, the development of the synthesis of unsaturated deuterated lipids [53], and the purification of deuterated lipids from cell cultures [54], means that protein deuteration is not always required in order to achieve the required neutron contrast.

In mammalian cells, the inner mitochondrial membrane hosting HsDHODH consists mainly of phosphatidylcholine (38–45%), phosphatidylethanolamine (32–39%), cardiolipin (14–23%), and phosphatidylinositol (2–7%) lipids. The outer mitochondrial membrane also consists mostly of phosphatidylcholine (44–59%) and phosphatidylethanolamine (20–35%) but contains a significantly lower amount of cardiolipin (1–10%) and a higher proportion of phosphatidylinositol (~13%) [55,56]. There are also variations in lipid composition depending on the tissue and species. In rats, for example, the cardiolipin content is significantly higher in the liver and kidneys (9–20%) than in the brain, lungs, or heart, where it ranges from 2 to 8% [55]. The E. coli cytosolic membrane that EcDHODH [57] is associated with is composed of mainly phosphatidylethanolamine (76–77%), with phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin present at 11–12% each. Both the IMM and E. coli membranes are dominated by C16 and C18 acyl chain lengths, with the main differences being that E. coli membranes are more saturated and contain C17 cyclic fatty acids [58]. Cardiolipins, in particular, are mostly (~80%) composed of linoleic acyl chains in mammalian cells [59], whereas the acyl chains are primarily derived from palmitic acid in bacteria, such as E. coli [60].

As there are no published data on the interaction of DHODH with lipid membranes, we have focused on a selection of simple model membranes in order to begin to elucidate the relative membrane-binding strength of HsΔ29DHODH and EcDHODH and the dependence on the presence of ubiquinone and some of the lipids found in human mitochondria and the E. coli cytosolic membrane. Our results show that both of the enzymes bind to the membranes containing cardiolipin in the absence and presence of ubiquinone Q10, which is located at the center of the bilayers. EcDHODH binds more efficiently to the surface of simple bilayers consisting of 1-palmitoyl, 2-oleoyl phosphatidylcholine (POPC), and tetraoleoyl cardiolipin (TOCL) compared to HsΔ29DHODH. Q10 is located at the center of all of the lipid bilayers studied, including those prepared from POPC and TOCL, as well as those prepared from more complex lipid mixtures. We also show that both human and bacterial DHODH penetrate into the hydrophobic chain region of the outer lipid leaflet to meet the Q10, which remains in the central layer. We therefore show that the interaction between the enzymes and the membrane-embedded ubiquinone is mediated by enzyme penetration, and not by ubiquinone reorientation. The degree of enzyme penetration depends on the enzyme but also on the lipid composition of the bilayer. We hereby also highlight the importance of the lipid bilayer composition for the enzyme interaction.

2. Results

2.1. General Experimental Setup

All of the experiments were executed following the same protocol. First, the supported lipid membranes were formed in situ in the NR sample cell by vesicle fusion after characterizing each Si-SiO2 surface by NR measurements in D2O and H2O. The lipid bilayer reflectivity was measured in four buffer contrasts consisting of different fractions of heavy water (D2O, CM4 (66 vol% D2O), CMSi (38 vol% D2O), and H2O). The protein solutions were prepared by diluting 5–10 mg/mL protein stock solutions in H2O buffer (in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 10 vol% glycerol, pH 7.4) to 0.4 mg/mL in 10 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. For the D2O buffers, the pH was set to 7.0 in order to give a pD value of 7.4, since pD = pH + 0.4 at 25 °C. In D2O, this dilution scheme resulted in a minimum H2O content of 4–8 vol%. A total of 3 mL of protein solution was injected into the sample cell containing the lipid bilayer and the neutron reflectivity was measured after 30 min of incubation in the same solvent contrast, as well as after the sample cell was rinsed with buffer. Protein addition and rinsing were repeated in every contrast due to the protein interaction being partially reversible, as shown by our previous QCM-D measurements [43]. An overview of all of the bilayers and enzymes measured can be found in Supplementary Material Table S1. Previously published component volumes of the lipid constituents [61,62,63,64,65] were used to calculate the scattering length density (SLD) values shown in Table S2. Previously published amino acid molecular volumes [66] were used to calculate the SLD values for the proteins under study (Table S2) taking into account the exchange of protons with the solvent in each buffer contrast.

In all of the systems studied, addition of protein resulted in the formation of multiple protein layers (two to six) on top of the lipid bilayer. It should be noted, however, that these additional layers are very sparsely populated and consist mostly of water, and they are thus unlikely to influence the behavior of the inner protein layer. As we use D2O for contrast, we wanted to exclude the isotope effects on protein stability and aggregation and therefore tested the influence of the different contrasts (containing different amounts of D2O) on protein stability and aggregation. For this, we performed thermal stability experiments with nano differential scanning fluorimetry (nanoDSF) in different buffer contrasts. We could not find differences in the Tm values of the proteins in the different contrasts, or any signs of induced protein aggregation (Table S3). It is, however, possible that the formation of multiple protein layers is related to some nonspecific protein–protein interactions becoming evident due to the length of the experiments or the local protein concentration at the bilayer surface, but as it is unlikely to be physiologically relevant, we have mainly focused on the details of the first protein layer in contact with the lipid membranes and the degree of protein penetration into the lipid bilayer. For this reason, the terms “retention” and “binding strength” in this manuscript refer to the first protein layer that is in contact with the lipids. By binding strength, we refer to the observed amount of bound enzyme in the first protein layer, and by retention, we do not refer to the equilibrium dissociation constant, but rather to whether or not the bound protein is displaced by rinsing with buffer.

2.2. EcDHODH Binds the Surface of POPC/TOCL Membranes More Strongly Than HsΔ29DHODH, but Penetrates into the Bilayer Less Efficiently

Our previous results, which were obtained with quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring (QCM-D) studies [43], showed that both HsΔ29DHODH and EcDHODH have very low binding to pure POPC lipid bilayers and bind reversibly, and that TOCL is a prerequisite for more stable binding. We therefore decided to investigate the structural basis of their interaction with the bilayers containing POPC and 10 mol% TOCL using NR. In the inner mitochondrial membrane of mammalian cells, the fraction of cardiolipin ranges from 10 to 20 mol% [55]. In order to ensure enough neutron contrasts to determine the structure of the protein-containing bilayers, we measured the binding of HsΔ29DHODH to the bilayers that were prepared with either hydrogenous POPC or chain-deuterated POPC (d63-POPC) [67] in combination with hydrogenous cardiolipin (TOCL). Measuring these bilayers in four different buffer solution contrasts before and after protein addition and after rinsing allowed us to determine the lipid composition (amount of TOCL and Q10) and solvent fraction in each layer in addition to the lipid and protein layer thicknesses. The analysis procedure is described in the Materials and Methods section. We also investigated the binding of EcDHODH to a bilayer that was prepared from POPC and TOCL.

The NR data from the bilayers consisting of POPC and TOCL were modeled using the following four laterally homogenous layers: inner lipid headgroups, inner lipid chains, outer lipid chains, and outer lipid headgroups. For the bilayer that were prepared with 90 mol% d63-POPC and 10 mol% TOCL (Table 1 and Table S4, and Figure 2), the selective deuteration allowed us to observe an asymmetric distribution of the two lipid species between the leaflets. A total of 10 mol% TOCL corresponds to 20.5 vol% of the total lipid chain volume, but the data could be best fitted by a model in which the inner membrane leaflet contains 14 ± 2 vol% TOCL (SLD = 5.4 ± 0.1 × 10−6 Å−2) and the outer leaflet 27 ± 2 vol% TOCL (SLD = 4.6 ± 0.1 × 10−6 Å−2), corresponding to a total TOCL content of 21 ± 2 vol%. This spontaneous asymmetry arises from the cardiolipin headgroup being negatively charged, making its interaction with the negatively-charged SiO2 surface less favorable. The bilayer had a surface coverage (total lipid volume fraction in the chain region) of 81 ± 3 vol%, indicating that the surface had 19 ± 3 vol% bilayer-free area containing solvent. The data from the bilayers that were prepared using hydrogenous lipids (90 mol% POPC and 10 mol% TOCL) could be fitted using a similar structure (Table S5 and Figure S1) with a surface coverage of 91 ± 2 vol%.

Table 1.

Parameters corresponding to the best fits to the data from d63-POPC/TOCL membranes before and after addition of HsΔ29DHODH, as displayed in Figure 2. τ = layer thickness, ρ = coherent neutron scattering length density (SLD) of the layers without the solvent contribution, φ = solvent volume fraction, σ = σ-value of a gaussian interfacial roughness between each layer and the previous layer. For simplicity, only the parameters corresponding to the inner protein layer are displayed. Fitting uncertainties are given for the most sensitive contrast. Detailed information is provided in Table S4.

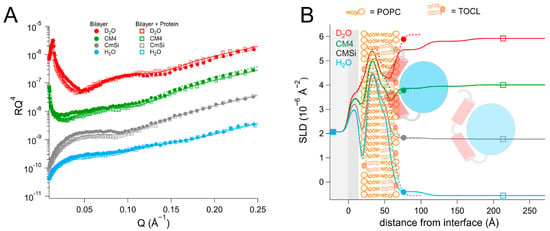

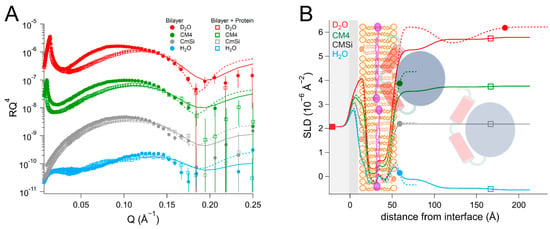

Figure 2.

(A) Reflectivity curves (data from INTER, ISIS) and (B) SLD profiles for d63-POPC/TOCL membranes before and after addition of HsΔ29DHODH, with a schematic representation of the model structure. POPC molecules are shown in brown (hollow heads, two tails). TOCL molecules are depicted in orange (filled heads, four tails). The α1-α2 microdomain of the protein is shown in red and the catalytic domain is depicted in blue.

The addition of HsΔ29DHODH to the d63-POPC/TOCL bilayer resulted in the formation of two very hydrated protein layers on top of the lipid bilayer of 43 ± 5 Å and 60 ± 15 Å thickness. The re-addition of protein solutions after each buffer rinse in each of the contrasts gave rise to small variations in the solvent content and the thickness of the protein layers, but most of the protein remained bound. The repeated protein addition and rinsing did not result in significant changes in the lipid bilayer coverage. Most notably, the protein binding resulted in a clear decrease in the SLD value of the outer lipid chain layer, but no change in the inner lipid layer. This indicates that some of the protein penetrates into the lipid chains, as the values cannot be explained by the redistribution of the lipids. The SLD of the outer chain layer corresponds to 37 ± 8 vol% protein, relative to the lipid chains, and makes up 29 ± 8 vol% of the whole layer, taking into account the solvent fraction (21 ± 3 vol%). Protein SLD values vary with solvent contrast due to proton exchange with the solvent, and in this case, although the solvent variation is close the fitting uncertainty in the lipid chain region, including it does lead to an improvement in the quality of the fits. However, some of the SLD change can also arise from a disturbed lipid packing due to the protein penetration. In the outer headgroups that contain 44 ± 5 vol% solvent, the resolution to the protein is poorer but the data are consistent with the same absolute protein volume fraction as in the chains (29 ± 8 vol%). The binding of HsΔ29DHODH to the hydrogenous (POPC/TOCL) bilayers was measured in two solvent contrasts (Table S5 and Figure S1) and could also be modeled using a model of two adsorbed protein layers containing 93 ± 3 and 98 ± 3 vol% solvent, but without explicitly including protein penetration due to the poorer contrast.

The dimensions of HsΔ29DHODH, according to the crystal structure corresponding to the ligand-free enzyme (PDB ID: 2PRM) [15], are approximately 45 Å on the vertical axis (with the alpha-helical domain pointing downwards) and 53 Å on the horizontal axis (Figure 1B). The approximate volume of a single protein molecule based on the amino acid composition (Table S2) is 49165 Å3. The addition of HsΔ29DHODH on the d63-POPC/TOCL bilayer results in the adsorption of 2.8 ± 1.1 × 105 molecules/µm2 and a protein–lipid ratio of 1:44 in the outer leaflet (based on the most sensitive contrast).

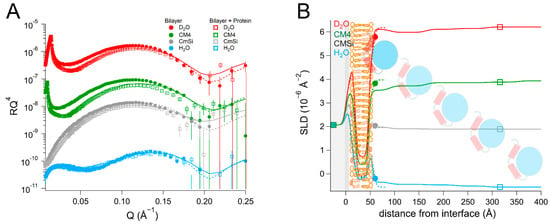

The addition of the bacterial enzyme (EcDHODH) to a POPC/TOCL bilayer (Table 2 and Table S6, and Figure 3) also resulted in a change in the SLD of the lipid chain region that could not be explained only by the presence of solvent or lipid rearrangement. Some of the protein initially occupied the defects in the lipid bilayer and displaced the solvent in the H2O contrast, but in all of the subsequent contrasts, the lipid–protein interaction could be modelled in a manner similar to that of the human enzyme, assuming that the protein binds as several layers on top of the lipid bilayer and penetrates into the outer lipid chains. The first protein layer is more densely populated than in the case of the human enzyme, displaying a solvent content of 72 ± 2 vol%, but the penetration into the outer lipid chain layer is weaker, where it accounts only for 8 ± 3 vol% of the lipid chain volume. This suggests that there is a stronger interaction of the bacterial protein with the lipid bilayer surface compared to HsΔ29DHODH, but a weaker interaction with the lipid chains. However, an increased solvent content of 19 ± 2 vol% was also observed in the lipid chains, indicating that the protein removes some of the lipids (9 vol%) upon rinsing, and that some of the protein may be removed along with them. However, the protein–lipid interaction is less reversible than for the truncated human enzyme, as the enzyme and lipid amounts remain stable between subsequent contrasts/rinsing. The innermost protein layer has a thickness of 46 ± 5 Å, while the subsequent layers can be modeled with a thickness of 55 ± 15 Å each and an increasing solvent content.

Table 2.

Parameters corresponding to the best fits to the data from POPC/TOCL membranes before and after addition of EcDHODH, as displayed in Figure 3. For simplicity, only the parameters corresponding to the inner protein layer are displayed. Fitting uncertainties are given for the most sensitive contrast. Detailed information is provided in Table S6.

Figure 3.

(A) Reflectivity curves (data from D17, ILL) and (B) SLD profiles for POPC/TOCL membranes before and after addition of EcDHODH, with a schematic representation of the model structure. POPC molecules are shown in brown (hollow heads, two tails). TOCL molecules are depicted in orange (filled heads, four tails). The α1-α2 microdomain of the protein is shown in red and the catalytic domain is depicted in blue.

2.3. DHODH Penetration into the Lipid Hydrophobic Region Mediates Interaction with Q10 Located at the Center of POPC/TOCL Bilayers

We proceeded to investigate the location and the effect of Q10 on the binding of DHODH in POPC and TOCL bilayers. In order to ensure enough contrast to detect the location of the ubiquinone, we measured the binding of HsΔ29DHODH to bilayers prepared with either POPC or d63-POPC in combination with TOCL and Q10. We then compared the binding of EcDHODH to HsΔ29DHODH to a bilayer that was prepared from POPC, TOCL, and Q10.

The d63-POPC/TOCL/Q10 bilayer could not be modelled using a four-layer model, as was the case for the d63-POPC/TOCL bilayers. It was therefore modelled using the following five layers (Table 3 and Table S7, and Figure 4): inner lipid heads, inner lipid chains, ubiquinone + lipid chains, outer lipid chains, and outer lipid heads. d63-POPC and TOCL could be assumed to be asymmetrically distributed between the inner and outer leaflets, as observed in the case of the d63-POPC/TOCL bilayers. The inner lipid chains displayed an SLD of 5.4 ± 0.2 × 10−6 Å−2 (corresponding to 86 ± 3 vol% POPC and 14 ± 3 vol% TOCL) and the outer lipids chains showed an SLD of 4.4 ± 0.2 × 10−6 Å−2 (71 ± 3 vol% POPC and 29 ± 3 vol% TOCL), which are in very good agreement with the SLD values corresponding to the d63-POPC/TOCL bilayers. Ubiquinone was found to be concentrated in a separate layer in the middle of the bilayer, which was 4 ± 1 Å thick and consisted of 51 ± 5 vol% Q10 and 49 ± 5 vol% phospholipid chains based on the SLD value corresponding to the best fit (2.7 ± 0.2 × 10−6 Å−2) in the most sensitive contrast. The total amount of ubiquinone in this layer correlates well with the 10 mol% added to the lipids. The inner and outer lipid chain layer thickness values were also smaller than in the absence of Q10, which is consistent with part of the lipid chains being located in the middle ubiquinone-rich layer. The solvent content in the entire lipid chain region was 9 ± 1 vol%, corresponding to a 91 ± 1 vol% bilayer coverage, whereas the total bilayer thickness was 49 ± 1 Å. A ubiquinone-rich middle layer was also observed in the POPC/TOCL/Q10 bilayers (Table S8 and Figure S2), in which Q10 accounted for 51 ± 13 vol%, with the uncertainty being larger due to the lower contrast between Q10 and the non-deuterated phospholipid chains. The bilayer coverage was 95 ± 1 vol% and the thickness was 49 ± 1 Å. In summary, these results indicate clearly that Q10 localizes to the center of the bilayer.

Table 3.

Parameters corresponding to the best fits to the data from d63-POPC/TOCL/Q10 membranes before and after addition of HsΔ29DHODH, as displayed in Figure 4. For simplicity, only the parameters corresponding to the inner protein layer are displayed. Fitting uncertainties are given for the most sensitive contrast. Detailed information is provided in Table S7.

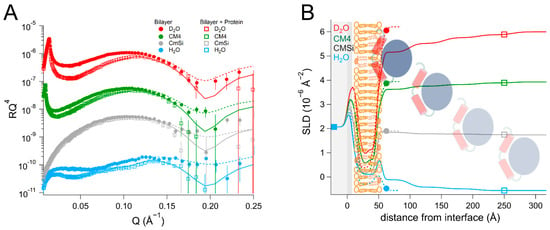

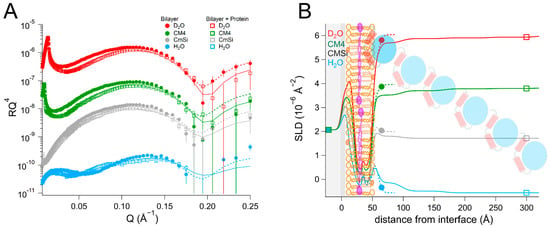

Figure 4.

(A) Reflectivity curves (data from INTER, ISIS) and (B) SLD profiles for d63-POPC/TOCL/Q10 membranes before and after addition of HsΔ29DHODH. POPC molecules are shown in brown (hollow heads, two tails). TOCL molecules are depicted in orange (filled heads, four tails). The α1-α2 microdomain of the protein is shown in red and the catalytic domain is depicted in blue. Ubiquinone molecules are represented in purple (filled heads, long tails).

The addition of HsΔ29DHODH to the d63-POPC/TOCL/Q10 bilayer resulted in the formation of three protein layers on top of the lipids, the first layer had a thickness of 36 ± 5 Å and 70 ± 2 vol% solvent in the most sensitive contrast (D2O). In the first contrast measured (H2O), the protein appeared to penetrate into the solvent-filled defects in the bilayer, as the solvent fraction decreased to 0 ± 2 vol%, while the inner and outer chain SLD values decreased to 5.0 ± 0.2 × 10−6 Å−2 and 4.0 ± 0.2 × 10−6 Å−2, respectively, which corresponds to 11 vol% of the bilayer being composed of protein. In subsequent contrasts, the protein addition resulted in a decrease in the SLD of the outer lipid chain layer (from 4.4 ± 0.2 × 10−6 Å−2 to 4.0 ± 0.2 × 10−6 Å−2 in D2O) and an SLD variation with contrast that is consistent with 29 ± 14 vol% DHODH relative to the lipids. The best fit suggests, however, that the SLD of the middle ubiquinone layer remains unchanged (2.7 ± 0.2 × 10−6 Å−2). These SLD changes suggest that the protein penetrates the outer lipid chain region but that no ubiquinone reorientation or migration occurs towards the lipid–water interface from the middle layer. The protein binding does not seem to remove a significant portion of the lipid bilayer, as the bilayer coverage remains stable at 89 ± 2 vol%. As in the ubiquinone-free d63-POPC/TOCL bilayer, protein binding could also be modeled in the outer lipid headgroups with the same absolute volume fraction as found in the lipid chain layer.

The results obtained with the fully hydrogenous bilayers (POPC/TOCL/Q10) upon HsΔ29DHODH binding (Table S8 and Figure S2) are also consistent with uniform protein penetration into the outer lipid chain region. The SLD of the lipid chain region increases from −0.27 ± 0.1 × 10−6 Å−2 to −0.17 ± 0.1 × 10−6 Å−2, while the SLD of the inner lipid region remains unchanged. This suggests that there is only a small amount of protein penetration into the outer lipid chain region, 3 ± 3 vol% relative to the lipids. There is no evidence of ubiquinone migration, as the SLD of the ubiquinone middle layer remains unchanged. The protein addition also results in the formation of three protein layers on top of the lipid bilayer. The innermost protein layer is 38 ± 5 Å thick and contains 78 ± 2 vol% water in the most sensitive contrast (D2O). The results obtained with the hydrogenous bilayers also confirmed that the lipid chain region of the bilayer did not become significantly thicker or thinner as a result of protein addition.

Rinsing with the buffer resulted in the removal of 33 ± 10% of the protein that was initially bound to the d63-POPC/TOCL/Q10 bilayer and the solvent content of the innermost protein layer increased to 80 ± 2 vol% in the most sensitive contrast. Rinsing removed 45 ± 16% of the protein initially bound to the POPC/TOCL/Q10 bilayer. Rinsing did not result in additional changes in the SLD values of the ubiquinone and outer lipid chain regions for any of the datasets studied.

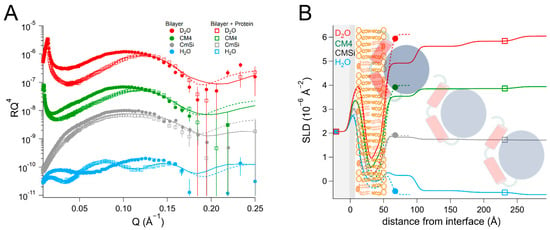

In the POPC/TOCL/Q10/EcDHODH system (Table 4 and Table S9, and Figure 5), protein addition resulted in the formation of two layers on top of the lipid bilayer, the first with a thickness of 39 ± 5 Å, and the outer layer had a thickness of 73 ± 15 Å. The solvent in the protein inner layer amounted to 81 ± 2 vol% in all of the contrasts, suggesting a stable protein–lipid interaction. As with the human enzyme, the SLD of the ubiquinone middle layer remained unchanged but the SLD of the outer lipid chain region increased to 0.057 ± 0.2 × 10−6 Å−2 in the D2O contrast, with an SLD variation with contrast indicating that 10 ± 8 vol% relative to the lipids of protein penetrates into the chains. The protein binding also resulted in some of the lipids being removed, as indicated by an 8 ± 2 vol% decrease in the bilayer coverage. Rinsing removed very little of the initially bound protein and the solvent content remained almost unchanged (85 ± 2 vol% in H2O). No major changes were observed in the SLD values of the bilayer after rinsing.

Table 4.

Parameters corresponding to the best fits to the data from POPC/TOCL/Q10 before and after addition of EcDHODH, as displayed in Figure 5. For simplicity, only the parameters corresponding to the inner protein layer are displayed. Fitting uncertainties are given for the most sensitive contrast. Detailed information is provided in Table S9.

Figure 5.

(A) Reflectivity curves (data from INTER, ISIS) and (B) SLD profile for POPC/TOCL/Q10 bilayers before and after addition of EcDHODH. POPC molecules are shown in brown (hollow heads, two tails). TOCL molecules are depicted in orange (filled heads, four tails). The α1-α2 microdomain of the protein is shown in red and the catalytic domain is depicted in blue. Ubiquinone molecules are represented in purple (filled heads, long tails).

Compared to the binding of EcDHODH to membranes consisting only of POPC and TOCL (Table 2), the incorporation of Q10 slightly increased the amount of the enzyme penetrating into the lipid bilayer, while decreasing the overall amount of enzyme on the bilayer surface, as only two protein layers were observed in the presence of Q10. The protein density in the innermost layer was similar.

2.4. The Presence of Q10 Does Not Increase Protein Binding Strength or Retention in Complex Lipid Bilayers

We then proceeded to investigate the interaction of HsΔ29DHODH with bilayers of increased lipid complexity. For this we used a phospholipid mixture extracted as described in [48] from the yeast Candida glabrata [68], from which we prepared membranes in the presence and absence of 10 mol% Q10. The phospholipid composition of this mixture was (mol%) as follows: 52% phosphatidylcholine (PC), 27% phosphatidylserine (PS), 14% phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), 4% phosphatidylinositol (PI), and 3% cardiolipin (CL). The fatty acid distribution (mol%) was as follows: 40% C18:1, 38% C16:1, 11% C18:0, 6% C16:0, 3% C16:2, 4% C18:2, and 2% C18:3, as reported in [69]. For comparison, the molar lipid composition of the inner mitochondrial membrane of mammalian cells is approximately 45% PC, 30% PE, 20% CL, and the rest corresponds to other lipids (mostly PI) [55]. The average headgroup lipid volume of the yeast lipid mixture calculated from the composition is 305 Å3 and that of the tails is 942 Å3. The data from this bilayer could be fitted using the expected SLD values for both the lipid chains and the headgroups (Table 5 and Table S10, and Figure 6). The theoretical SLD values for the lipid chains and headgroups are listed in Table S2. In the fits, the different lipid classes were assumed to be symmetrically distributed between the inner and outer leaflets to within the sensitivity to the lipid composition, in the absence of selective deuteration to detect asymmetry. The bilayers that were prepared with Q10 could be modelled using a similar model of five layers (inner heads, inner chains, middle layer, outer chains, and outer heads), as for POPC/TOCL bilayers. The middle ubiquinone rich layer was also found to be of the same thickness, 4 ± 1 Å, and composed of 57 ± 14 vol% Q10 (Table 6, Table S11, and Figure 7).

Table 5.

Parameters corresponding to the best fits to the data from Candida glabrata membranes before and after addition of HsΔ29DHODH, as displayed in Figure 6. For simplicity, only the parameters corresponding to the inner protein layer are displayed. Fitting uncertainties are given for the most sensitive contrast. Detailed information is provided in Table S10.

Figure 6.

(A) Reflectivity curves (data from D17, ILL) and (B) SLD profiles for yeast membranes before and after addition of HsΔ29DHODH. The α1-α2 microdomain of the protein is shown in red and the catalytic domain is depicted in blue. The complex mixture of the yeast membranes is schematically depicted here using the same image as for POPC/TOCL in previous figures.

Table 6.

Parameters corresponding to the best fits to the data from Candida glabrata bilayers supplemented with Q10 before and after addition of HsΔ29DHODH, as displayed in Figure 7. For simplicity, only the parameters corresponding to the inner protein layer are displayed. Fitting uncertainties are given for the most sensitive contrast. Detailed information is provided in Table S11.

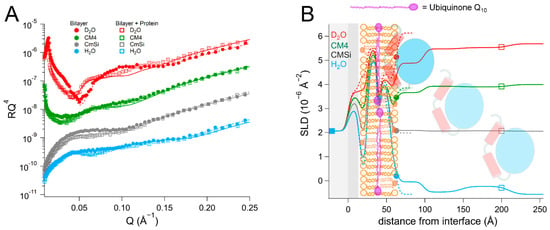

Figure 7.

(A) Reflectivity curves (data from D17, ILL) and (B) SLD profiles for yeast lipid bilayers supplemented with Q10 before and after addition of HsΔ29DHODH. The α1-α2 microdomain of the protein is shown in red and the catalytic domain is depicted in blue. Ubiquinone molecules are represented in purple (filled heads, long tails). The complex mixture of the yeast membranes is schematically depicted here using the same image as for POPC/TOCL in previous figures.

The addition of HsΔ29DHODH to the yeast phospholipid bilayer resulted in the formation of several increasingly hydrated protein layers on top of the bilayer. The innermost layer had a thickness of 35 ± 5 Å and solvent content of up to 70 ± 2 vol%. The outer protein layers were 60 ± 15 Å to 75 ± 15 Å thick. As was the case for the synthetic lipid bilayers, the protein penetrated through the outer headgroups and into the outer lipid chains. The protein accounted for 10 ± 5 vol% of the volume in the mixed lipid chain/protein layer. The protein addition also resulted in some lipid removal, as indicated by the solvent content in the lipid chain region, which increased from 2 ± 1 vol% to 15 ± 1 vol%. In the case of the bilayer containing Q10, the protein resulted in very similar layers and penetration profile into the lipid bilayer as without Q10 (Table 5 and Table S10, and Figure 6).

The rinsing removed a large fraction of the protein that was initially bound to bilayers both with and without ubiquinone. These results also suggest that, in contrast to what we observed for the bilayers that were prepared with synthetic lipids, ubiquinone does not increase the binding of HsΔ29DHODH to more complex bilayers containing other lipids. Compared to the bilayers consisting of synthetic lipids (POPC, TOCL), the bilayers that were prepared with lipid mixtures extracted from yeast resulted in a higher degree of HsΔ29DHODH binding. In other words, the lipid composition does have a major effect on protein binding strength.

Finally, we investigated the interaction between the DHODH from E. coli and a mixture of synthetic lipids mimicking the composition of the bacterial plasma membrane [70]. The composition (mol%) of the lipid mixture used was as follows: 40% POPC, 35% POPE, 13% POPG, and 12% TOCL. In this case, the data from the resulting bilayer (Table 7 and Table S12, and Figure 8) could be fitted with the expected SLD values, the bilayer coverage was 91 ± 1 vol%, and the total thickness was 50 ± 1 Å.

Table 7.

Parameters corresponding to the best fits to the data from bacterial mimic membranes before and after addition of EcDHODH, as displayed in Figure 8. For simplicity, only the parameters corresponding to the inner protein layer are displayed. Fitting uncertainties are given for the most sensitive contrast. Detailed information is provided in Table S12.

Figure 8.

(A) Reflectivity curves (data from D17, ILL) and (B) SLD profiles for bacterial mimic membranes before and after addition of EcDHODH. The α1-α2 microdomain of the protein is shown in red and the catalytic domain is depicted in blue. The mimic mixture of the bacterial membrane is schematically depicted here using the same image as for POPC/TOCL in previous figures.

After protein addition, EcDHODH was observed to form three layers of increasing hydration on top of the lipid bilayer. The inner protein layer had a thickness of 40 ± 5 Å and a solvent content of 63 ± 2 vol% in the final contrast measured (D2O). The outer protein layers were between 55 ± 5 Å and 60 ± 5 Å thick and had higher levels of hydration. The protein penetrated into the outer lipid chains and accounted for 25 ± 6 vol% relative to the lipids. This is considerably more than the amount of EcDHODH penetrating into the POPC/TOCL and POPC/TOCL/Q10 and indicates that the other lipids native to E. coli (POPE and POPG) are important for binding. The rinsing removed no significant amount of the initially bound protein.

In summary, the only common model describing all of the experimental data sets features the homogeneous penetration of HsΔ29DHODH and EcDHODH into the outer lipid leaflet. The experiments presented above suggest that both the presence of the substrate Q10 and the composition of the lipid bilayer play a determining role for the relative binding strength of the enzyme to the bilayer.

3. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first in situ structural investigation of the interaction between lipid bilayers and Class II DHODHs, in which both the lipid and the protein structures are resolved in one dimension. This provides the benefit of observing how the lipid bilayer structures differ based on their composition and how this influences the interaction with the protein.

To date, the interaction of E. coli DHODH with mixed DOPC/Triton X-100 vesicles has been investigated by electronic spin resonance [71] and the ability of N-terminally Class II truncated Plasmodium falciparum DHODH to bind to PC and PE liposomes was shown by size-exclusion chromatography [72]. Furthermore, the α1-α2 microdomain in HsDHODH, as an isolated synthetic peptide, has also been studied. Using this peptide, spectroscopic measurements indicate that the α1-α2 microdomain assumes a different conformation in detergent micelles and phospholipid vesicles [37].

These studies indicate that DHODHs lacking transmembrane domains, such as the one from E. coli, can interact with lipid bilayers and that the α1-α2 microdomain undergoes conformational changes depending on the interaction partner. Therefore, it is likely that the lipid composition plays a major role on the protein–membrane interactions. In this study we set out to investigate this phenomenon. A second question that we addressed is how DHODHs belonging to Class II might interact with the co-substrate, ubiquinone, and how this affects protein–membrane interactions.

By using multidimensional neutron contrast variation of the lipids and the aqueous solvent, we have directly observed the location of ubiquinone in the bilayers, consistent with previous experiments with neutron diffraction [38], showing that ubiquinone tends to localize at the center of the lipid bilayer in multilamellar lipid stacks and fills the interstitial space in the inverse hexagonal HII phase of POPE [73]. Our results clearly indicate a perpendicular orientation of Q10 relative to the phospholipids. We could show this location in a variety of bilayers, including those that were prepared from complex lipid mixtures derived directly from a eukaryotic organism (Candida glabrata), translating previous findings with two synthetic lipids alone [38] to a more complex and physiologically relevant setting. Our most significant finding is that the binding of both HsΔ29DHODH and EcDHODH to the surface of the lipid bilayers does not result in the migration or reorientation of ubiquinone from the middle layer towards the membrane–water interface where the protein is located. Instead, our data show that, upon binding to the lipid bilayer, both of the enzymes penetrate into the outer lipid chain region, both in the absence and presence of Q10. A direct interaction between Q10 and the enzyme is suggested by the increased retention upon rinsing that HsΔ29DHODH displays on POPC/TOCL bilayers containing Q10 in comparison to those without. This effect was both observed in our study here and in our previous study [43] using QCM-D. The location of ubiquinone at the center of the lipid bilayers and the lack of observable reorientation in the bilayer to bind DHODH are consistent with its large molecular size and branched chain structure, which make it poorly soluble in the phospholipids.

In most cases, the inner protein layer on the surface of the lipid bilayer is somewhat thinner (35–46 Å) than the protein dimensions in the crystal structure and suggest the formation of a monolayer of the protein. However, according to the data analysis, the proteins also penetrate into the outer lipid leaflet by up to 23–24 Å, which would make the total thickness of the first protein layer clearly greater than the crystal structure suggests. Two possible scenarios could explain this. The crystallographic data indicates the α1-α2 microdomains of both of the enzymes (Figure 1B) are connected to their respective core catalytic domains by potentially flexible loops. Movements in this loop have been shown upon inhibitor binding to N-terminal truncated HsDHODH and reveal the possibility of conformational flexibility in this region of DHODHs [15]. Although there are no published reports of this to date, it is likely that the amphipathic α1-α2 microdomain penetrates into the outer lipid chain region, whereas the rest of the catalytic domain remains on the surface of the bilayer, such a conformational rearrangement is facilitated by the flexible loop, as mentioned previously. Alternatively, it is possible that two partially overlapping layers of protein are in contact with the lipid bilayer, one penetrating into the lipids and one on the surface. Our NR data is consistent with both of these scenarios, however it could also be explained by a combination of α1-α2 microdomain penetration and a second, partially overlapping protein layer on the membrane surface. The higher thicknesses of the outer protein layers are less defined, due to the very high solvent fraction (>90 vol% water) and do not necessarily portray individual protein layers.

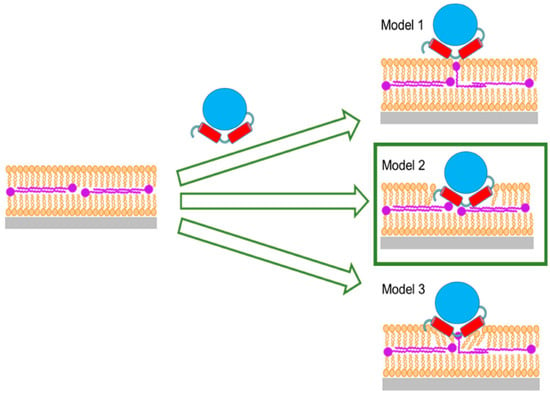

The observation that both HsΔ29DHODH and EcDHODH clearly penetrate into the lipid bilayer to a significant extent is new, to our best knowledge, and indicates that the interaction of the α1-α2 microdomain with lipids has perhaps a larger role to play in the membrane–DHODH interaction than previously thought. This is particularly interesting in the context of the present comparison of the naturally soluble EcDHODH for which this is the main interaction with membrane lipids, with the truncated HsΔ29DHODH, which in vivo has a transmembrane domain anchoring it to the IMM. The differences that were observed in the membrane-binding strength and reversibility of the lipid interaction for the two enzymes support a stronger ability of EcDHODH to bind to the bacterial plasma membrane using only the alpha-helical domain, whereas HsΔ29DHODH also requires the TM to remain in the IMM. The model of enzyme penetration towards the ubiquinone located at the center of lipid bilayers (Figure 9) could be relevant for other enzymes that use ubiquinones as electron acceptors. Ubiquinones are found in all membranes, but Q10 is the key node in the mitochondrial respiratory chain and a substrate for other enzymes comparable to DHODH, such as succinate dehydrogenase, glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, or electron transfer flavoprotein coenzyme Q, located at the IMM [74,75]. In summary, our results provide evidence suggesting that the protein–ubiquinone interaction is facilitated by penetration of the enzyme into the outer lipid chain region (Model 2 in Figure 9), and, not to any degree observable in our experiments using NR, by migration of ubiquinone from the middle layer towards the outer lipid chain with enzyme partially, or not at all penetrating.

Figure 9.

Suggested models for the interaction of Class II DHODHs with ubiquinone. Model 1: Q10 bends up and reaches toward the enzyme at the outside of the lipid bilayer. Model 2: The enzyme penetrates the whole outer lipid bilayer leaflet to reach the Q10 at the center of the bilayer. Model 3: The enzyme partially penetrates the outer lipid bilayer leaflet and Q10 bends up and reaches towards the enzyme. Model 2, marked by a green box, is the only scenario supported by our data.

The presence of ubiquinone increases the binding of HsΔ29DHODH to bilayers consisting of synthetic lipids (POPC, TOCL), as indicated by a more densely populated innermost protein layer (containing less solvent), which is also more stable, as indicated by a lower degree of protein removal by rinsing. Lipid composition also has an effect on the binding of HsΔ29DHODH to the lipid bilayers. The bilayers consisting of a eukaryotic phospholipid mixture that were derived from yeast display a significantly higher protein binding ability compared to the bilayers that were prepared from synthetic lipids. However, incorporation of Q10 into bilayers prepared with this complex mixture of lipids does not result in a significantly increased binding of the enzyme or a higher retention, as is the case with synthetic lipid bilayers. Our results are consistent with previous studies using non-denaturing electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (nESI-MS) that have inferred that an N-terminally truncated HsDHODH, resembling our HsΔ29DHODH, displays a higher relative binding to lipids, such as TOCL and POPE, compared to POPC [40], as they are detected by MS in protein–lipid complexes.

We previously demonstrated, by using QCM-D experiments, that both HsΔ29DHODH and EcDHODH bind much more strongly to POPC bilayers that contain 10 mol% of TOCL, whereas in its absence the binding of both of the enzymes is reversible [43]. As the lipid chains are similar in both POPC and TOCL, this suggests that the cardiolipin headgroup is predominantly responsible for this effect. We therefore focused, in this study, on the effect of the lipid headgroups and the electrostatic interaction with the enzyme, by matching the acyl chains of the CL, PE, and PG to the POPC-based samples. The composition of the yeast lipid bilayer that was used was 52 mol% phosphatidylcholine (PC), 27 mol% phosphatidylserine (PS), 14 mol% phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), 4 mol% phosphatidylinositol (PI), and 3 mol% cardiolipin (CL) [69], and the fatty acid composition of the mixture was as follows (mol%): 40% oleic, 38% palmitoleic, 11% stearic, 6% palmitic, 4% linoleic, and 2% linolenic [69]. The CL in C. glabrata has the native acyl chain distribution similar to the overall mixture, apart from the increased linoleic acid (37.4% oleic, 33.7% palmitoleic, 11.3% linoleic, 9.1% palmitic, and 8.6% stearic). Compared to the 90 mol% POPC/10 mol% TOCL and the 80 mol% POPC/10 mol% TOCL/10 mol% Q10 bilayers, the yeast lipid mixture contains fewer neutral lipids (POPC) and more negatively-charged lipids, such as PS and CL. In line with what has been suggested by Costeira-Paulo et al. [40], we hypothesize that the electrostatic interactions between these negatively-charged lipid headgroups and the cationic residues present in the amphipathic α1-α2 microdomain of HsΔ29DHODH are likely to be the main drivers for protein–membrane interaction. However, as there are also differences in the lipid chain composition of the cardiolipins found in human mitochondria and in E. coli, with the latter being more saturated, an additional role for the lipid chains in the binding that was observed here for the two truncated enzymes can certainly not be excluded and deserves to be investigated in future studies.

Our results indicate that the bacterial EcDHODH displays a higher degree of binding to POPC and TOCL compared to the truncated human enzyme (HsΔ29DHODH). The interaction between the bacterial enzyme and the lipids is both stronger and more stable. The presence of ubiquinone in the lipid bilayer does not significantly increase the binding of EcDHODH. The lipid complexity does have an effect on EcDHODH binding, as its binding to bilayers, mimicking the composition of the bacterial plasma membrane (i.e., containing POPE and POPG), is even higher compared to only POPC and TOCL.

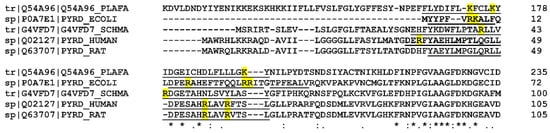

In order to examine the structural features of Class II DHOHDs, we searched the UniProt Database (accessed 16 December 2020) for Class II DHODHs with available X-ray crystal structures using the following query search in PDB: “dihydroorotate dehydrogenase quinone database: (type:pdb)”. From the returned eight hits, three (the DHODHs from Eimeria tenella, Helicobacter pylori, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis) had obsolete (not available) PDB entries, or did not cover the full α1-α2 microdomain. The remaining five sequences were used to perform a multiple sequence alignment (Figure 10 and Figure S3).

Figure 10.

Partial multiple sequence alignment of the N-terminal region of Class II DHODHs, of which a crystal structure including the α1-α2 microdomain is available (the full alignment can be found in the Supplementary Material Figure S3). The alignment was performed with CLUSTAL OMEGA(1.2.4) [77]. PLAFA: Plasmodium falciparum PDB 6I55; ECOLI: Escherichia coli PDB 1F76; SCHMA Schistosoma mansoni PDB 6UY4; HUMAN: Homo sapiens PDB 2PRM; RAT: Rattus rattus PDB 1UUM. The respective UniProt identifiers for the amino acid sequences used in the alignment are given to the left of each row between vertical lines. Amino acid stretches corresponding to α1-α2 microdomain according to the PDB entries are underlined. Cationic amino acid residues in these regions are marked in yellow.

We hypothesize that the higher relative binding displayed by the bacterial enzyme may arise from the presence of an abundance of positively charged residues on the outer surface of the α1-α2 microdomain of EcDHODH (Arg7, Lys8, Arg17, Arg27, and Arg28), which are likely to be in direct contact with the lipid bilayer. This is supported by the comparison of the amino acid sequences in Figure 10. The truncated human enzyme also possesses cationic residues in the corresponding region, but they are fewer in number (Arg35, Arg56, and Arg60). Thus, the human enzyme may rely to a greater extent on the presence of the transmembrane domain in order to achieve a stable interaction with the lipid bilayer, as opposed to the bacterial enzyme, which lacks such a structure and is also in need of using other electron acceptors besides membrane-embedded ubiquinones.

It is, however, interesting to note that the distribution of the cationic residues in the α1-α2 microdomain does not seem highly conserved in the Class II DHODHs in Figure 10, spanning a wide evolutionary distance. This conclusion is in line with a recent comprehensive bioinformatics study by Sousa et al. [76]. None of the positively charged residues on the outer surface of the α1-α2 microdomain were pointed out as highly conserved in an alignment of 1062 Class II DHODH sequences, or the whole α1-α2 microdomain, was one of the least conserved regions of the enzymes. It might be that the N-terminal part of DHODH has evolved to match the lipid composition of its respective cellular environment. In eukaryotes, together with the mitochondrial location, Class II DHODH have acquired a transmembrane domain, that anchors their position to the outer IMM. What other functions and benefits this transmembrane domain might have, is still open for discovery.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1′,3′-bis[1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho]-glycerol sodium salt (TOCL), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE), and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) sodium salt (POPG) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Coenzyme Q10, Tris-HCl, trisodium citrate, NaCl, CaCl2, and D2O (>99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Stockholm, Sweden) and used without further purification. Chain-deuterated 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-d63-glycero-3-phosphocholine (d63-POPC) was synthesized by the Deuteration and Macromolecular Crystallography (DEMAX) [78] platform at the European Spallation Source (ESS), Lund, Sweden, as previously published [67]. Complex polar phospholipid mixtures (h3pol) were extracted and purified from cultures of Candida glabrata displaying increased sensitivity to Amphotericin B, using procedures described elsewhere [54,69]. Undoped 80 × 50 × 15 mm3 silicon single crystals, polished on the (111) face to a typical roughness of <3 Å, were purchased from Siltronix (Archamps, France). The silicon substrates were cleaned in an aqueous piranha solution (5:4:1 H2O/H2SO4/H2O2) for 15 min at 80 °C, followed by extensive rinsing with ultrapure water and UV/ozone cleaning with a Jelight 144 AX cleaner from Bridge Tronic (Costa Mesa, CA, USA) for 10 min.

4.2. Expression and Purification of Proteins

The proteins used in this study were produced as previously described [43]. Briefly, pET-26b plasmids bearing the cDNA for either HsΔ29DHODH or EcDHODH were transformed into E. coli TUNER(DE3) cells (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Bacteria were cultured in Terrific Broth (TB) to an OD600 of 0.6–0.8 units. At this point, the cultures were supplemented with 100 µM FMN (Sigma-Aldrich, Stockholm, Sweden) and protein expression was induced with 100 µM IPTG. Protein expression took place for 20 h at 18 °C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and disrupted using a French pressure cell at 18,000 psig (Glen Mills Inc., Clifton, NJ, USA). The proteins were purified by immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography on nickel sepharose (HisTrap HP, Cytiva Life Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden) columns, removal of the His-tag and by size-exclusion chromatography using Superdex 200 pg (Cytiva Life Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden). HsΔ29DHODH and EcDHODH preparations used had specific activities of 97 U/mg and 100 U/mg respectively, as determined by previously described methods [43].

4.3. Thermal Shift Assays (TSA)

HsΔ29DHODH and EcDHODH preparations used in NR experiments were used for TSA by nano differential scanning fluorimetry (nanoDSF) experiments. Here, we tested protein stability and aggregation in the four contrasts used in the NR experiments as follows: D2O, H2O, silicon-matched water (CMSi), and water matched to an SLD of 4 (CM4). The final protein concentration was 0.2 mg/mL and we used the same buffer composition as in the NR experiments, as described below.

The samples were loaded into a Prometheus NT.48 (NanoTemper Technologies GmbH, Munich, Germany) using standard grade capillaries. The samples were heated 1 °C/min, from 20 °C to 95 °C, and unfolding of the protein was analyzed with the ratio of the wavelengths measured at 350 nm and 330 nm (Tryptophan/Tyrosine shifts) and a laser power of 20%. From the resulting curves, the thermal unfolding transition midpoint Tm (°C), at which half of the protein population is unfolded, could be extracted.

4.4. Preparation of Small Unilamellar Vesicles

Lipid stocks, dissolved in a mixture of chloroform/methanol (9:1 v/v), were mixed in glass vials and dried under a stream of nitrogen. The resulting dry lipid film was resuspended, in either ultrapure water (R = 18.2 MΩ) or buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), to a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL The lipid films were allowed to hydrate for at least 30 min at room temperature. Small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were prepared by sonicating the resuspended lipids with a Vibra-Cell VCX 130 tip sonicator from Sonics & Materials Inc. (Newtown, CT, USA) for 5 min at 35% amplitude with a 10 s on/off cycle until the solutions became visibly clear.

4.5. Neutron Reflectivity Measurements

Experiments were conducted on the D17 reflectometer at the Institut Laue-Langevin, Grenoble, France [79,80] and on the INTER reflectometer at the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source of the STFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Didcot, UK [81,82]. Specular neutron reflection was measured on the D17 reflectometer using neutron wavelengths (λ) of 2–20 Å to record reflectivity profiles between 0.01 < Q < 0.25 Å−1, and a 1–20% variable wavelength resolution (dλ/λ), where Q = 4π sin θ/λ is the momentum transfer vector of the neutrons in the direction (z) perpendicular to the membrane–water interface, and the reflectivity R is the ratio of the reflected intensity IR to the incident intensity I0. Two incident angles θ (0.7° and 3.0°) were used to obtain the full reflectivity profiles, with the background scattering subtracted from the 2D detector images. On the INTER reflectometer, the incidence angles used were 0.7° and 2.3° and reflectivity profiles were recorded using neutron wavelengths in the range from 1 to 16 Å, covering a Q range from 0.009 to 0.3 Å−1 and an angular resolution dθ/θ of 4%. The background was not subtracted from INTER data and was fitted as part of the data analysis.

The structure of the Si-SiO2 surface was characterized in D2O and H2O prior to the addition of lipids. The lipid bilayers were formed in situ by means of the vesicle fusion method, as described previously [45,48]. Briefly, 3 mL of the vesicle solutions were injected immediately after sonication into the neutron reflectivity cells previously equilibrated at 30 °C. The vesicles were incubated for 30 min to allow then to fuse and spread over the crystal surface. After rinsing off the excess vesicles with buffer (10 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH or pD = 7.4) containing no CaCl2, each lipid membrane was characterized in the following four contrasts: D2O, H2O, silicon-matched water (CMSi), and water matched to a value of 4 × 10−6 Å−2 (CM4). The CMSi and CM4 contrasts were produced by mixing 38 vol% D2O and 62 vol% H2O, and 66 vol% D2O and 34 vol% H2O, respectively. Contrast changes were achieved by rinsing with 20 mL of the solvent using a Knauer 4P HPLC pump (KNAUER Wissenschaftliche Geräte GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Protein solutions (3 mL) in 10 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, and either pD or pH = 7.4, were injected over the lipid membranes at either 0.4 mg/mL, or stepwise at a concentration of 0.4 mg/mL and changes in reflectivity were recorded after a 30 min incubation period. The protein–lipid bilayers were characterized in each of the four contrasts (D2O, H2O, CM4, CMSi) after protein addition and after rinsing with buffer.

4.6. Data Evaluation

The neutron scattering length density profile [ρ(z)] of a lipid bilayer can be described by distinct regions corresponding to the polar head groups and hydrophobic acyl chains due to their chemical differences. Reflectivity analysis is based on modelling the thickness, scattering length density, solvent volume fraction, and interfacial roughness of typically three layers corresponding to the two lipid head groups and the central acyl chain region. In membranes containing lipids, water, and a protein, the scattering length density (ρlayer) is the sum of the molecular scattering length densities of the components ρi weighted by their volume fractions ϕi as follows:

ρlayer = ϕlipidρlipid + ϕwaterρwater + ϕproteinρprotein

Thus, when there are significant differences in the molecular scattering length densities of lipid, protein, and water, their volume fractions can be computed from the fitted scattering length density profile of the membrane by using contrast variation. Similarly, in the selective deuteration of one lipid in a binary mixture can be used to determine the lipid composition in the bilayer, and the distribution (symmetric/asymmetric) of the two lipids. We used multidimensional contrast variation of both lipids (deuterated and non-deuterated chains) and the buffer solutions to obtain several different neutron data sets of each membrane, which were analyzed simultaneously, maintaining constant structural parameters (thickness, solvent fraction, roughness) that are unaffected by the degree of deuteration. Varying the solvent D2O content allows the solvent volume fraction in the membrane to be determined, in addition to the lipid composition and ubiquinone location to be revealed by the lipid contrast variation. The Motofit program [83], an extension of the IGOR Pro analysis package (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA), was used for optical matrix modelling using the Abeles method [84] in order to calculate neutron reflectivity from the lipid/protein membranes and to refine the model until the best fit to the experimental data was achieved. The quality of the fits was judged by the agreement between the curves derived from the model and the measured data points, whilst attempting to minimize the global chi-squared value and using the constraints that, whenever possible, the solvent content in the lipid chain region was kept constant across different contrasts. The area per lipid molecule of the bilayer was constrained to be equal in the lipid headgroups and chains in each monolayer containing only lipids.

The sensitivity of each solvent contrast to each lipid contrast depends on the relative SLD differences, which gives a different fitting uncertainty for each parameter in different contrasts. The global fit and uncertainty are determined by the most sensitive contrast for each parameter, and these values are given in the results tables. Uncertainties in the fitted parameters (thickness, solvent fraction, SLD) were propagated to the calculated parameters (Awet, mol% of lipids/Q10/protein).

5. Conclusions

We have investigated two Class II DHODH, HsΔ29DHODH, and EcDHODH, in situ by neutron reflectometry and show, for the first time, the structural basis of their interaction with lipid membranes. Both of the enzymes interact with ubiquinone, that is exclusively located at the center of the lipid bilayers, by penetration into the outer membrane leaflet, without any detectable ubiquinone migration. The enzyme relative binding strength to the lipid bilayer and the degree of penetration depend on both the enzyme and the lipid composition of the bilayer, with cardiolipin, phosphatidylethanolamine, and phosphatidylglycerol, as well as other lipids present in mitochondria, promoting the interaction. This is, to our knowledge, the first time the membrane penetration of the enzymes lacking a transmembrane domain has been observed and points to a larger role of the alpha-helical domain in the membrane interaction than was previously thought. This initial study lays the foundation for further investigations probing the role of lipid headgroup and acyl chain composition, as well as mutations in the enzymes on the membrane interaction and enzyme activity.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials are available online at the following address: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms23052437/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.P.W.-K. and W.K.; methodology, J.M.O.R., H.P.W.-K., L.A.C., O.B., A.L., G.F. and W.K.; validation, J.M.O.R., H.P.W.-K. and W.K.; formal analysis, J.M.O.R., H.P.W.-K. and W.K.; investigation, J.M.O.R., H.P.W.-K., L.A.C., G.F. and W.K.; resources, H.P.W.-K. and W.K.; data curation, J.M.O.R., H.P.W.-K. and W.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.O.R., H.P.W.-K. and W.K.; writing—review and editing, J.M.O.R., H.P.W.-K., L.A.C., O.B., A.L., G.F. and W.K.; visualization, J.M.O.R.; supervision, H.P.W.-K., G.F. and W.K.; project administration, W.K.; funding acquisition, J.M.O.R., H.P.W.-K. and W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Thanks to Lund University, the Royal Physiographic Society of Lund, the Erik Philip-Sörensen Foundation, and the Jörgen Lindström Foundation for financial support.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Lund Protein Production Platform (LP3, www.lu.se/lp3) staff for providing technical support for many of the experiments. We thank Robin Delhom for the purification and analysis of the lipid composition of the complex phospholipid mixture (h3pol) from Candida glabrata. The synthesis of d63-POPC was carried out at the DEMAX Platform, as a result of proposal R45CD2AU at the European Spallation Source ERIC. The persistent identifier for the sample is doi:10.5281/zenodo.4896257. We thank the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source of the STFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Didcot, UK, and the Institut Laue-Langevin, Grenoble, France, for providing beamtime and for the use of the Partnership for Soft Condensed Matter laboratories at Institut Laue-Langevin.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Accession Numbers

Full-length HsDHODH sequence (Uniprot Q02127, PYRD_HUMAN) and E. coli DHODH (Uniprot P0A7E1, PYRD_ECOLI).

Abbreviations

| Proteins | |

| HsDHODH | human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase |

| HsΔ29DHODH | human N-terminal truncated dihydroorotate dehydrogenase |

| EcDHODH | dihydroorotate dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli |

| Phospholipid classes | |

| PC | phosphatidylcholine |

| CL | cardiolipin |

| PE | phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PG | phosphatidylglycerol |

| PS | phosphatidylserine |

| PI | phosphatidylinositol |

| Synthetic lipids | |

| POPC | 1-palmitoyl,2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidyl choline |

| d63-POPC | chain-deuterated POPC, 1-palmitoyl-d31, 2-oleoyl-d32-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine |

| TOCL | tetraoleoyl cardiolipin |

| POPE | 1-palmitoyl,2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine |

| POPG | 1-palmitoyl,2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylglycerol |

| POPS | 1-palmitoyl,2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylserine |

| POPI | 1-palmitoyl,2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylinositol |

| Other | |

| Q10 | ubiquinone Q10 |

| IMM | inner mitochondrial membrane |

| SLD | scattering length density |

| CM4 | buffer contrast-matched to SLD = 4.0 (66 vol% D2O and 32 vol% H2O) |

| CMSi | buffer contrast-matched to the silicon substrate SLD = 2.07 (38 vol% D2O and 62 vol% H2O) |

| ISIS | ISIS Pulsed Neutron and Muon Source, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Didcot OX11 0QX, United Kingdom |

| ILL | Institut Laue-Langevin, 71 Avenue des Martyrs, BP 156, 38042 Grenoble, France |

References

- Denis-Duphil, M. Pyrimidine biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: The ura2 cluster gene, its multifunctional enzyme product, and other structural or regulatory genes involved in de novo UMP synthesis. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1989, 67, 612–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.R.; Guy, H.I. Mammalian pyrimidine biosynthesis: Fresh insights into an ancient pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 33035–33038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermansen, R.A.; Mannakee, B.K.; Knecht, W.; Liberles, D.A.; Gutenkunst, R.N. Characterizing selective pressures on the pathway for de novo biosynthesis of pyrimidines in yeast. BMC Evol. Biol. 2015, 15, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löffler, M.; Fairbanks, L.D.; Zameitat, E.; Marinaki, A.M.; Simmonds, H.A. Pyrimidine pathways in health and disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2005, 11, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löffler, M.; Carrey, E.A.; Knecht, W. The pathway to pyrimidines: The essential focus on dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, the mitochondrial enzyme coupled to the respiratory chain. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2020, 39, 1281–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munier-Lehmann, H.; Vidalain, P.O.; Tangy, F.; Janin, Y.L. On dihydroorotate dehydrogenases and their inhibitors and uses. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 3148–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.A.G.; Calil, F.A.; Feliciano, P.R.; Pinheiro, M.P.; Nonato, M.C. The dihydroorotate dehydrogenases: Past and present. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 632, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnberg, O.; Rowland, P.; Larsen, S.; Jensen, K.F. Active site of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase A from Lactococcus lactis investigated by chemical modification and mutagenesis. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 16197–16205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørager, S.; Jensen, K.F.; Björnberg, O.; Larsen, S. E. coli dihydroorotate dehydrogenase reveals structural and functional distinctions between different classes of dihydroorotate dehydrogenases. Structure 2002, 10, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnberg, O.; Grüner, A.C.; Roepstorff, P.; Jensen, K.F. The activity of Escherichia coli dihydroorotate dehydrogenase is dependent on a conserved loop identified by sequence homology, mutagenesis, and limited proteolysis. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 2899–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knecht, W.; Bergjohann, U.; Gonski, S.; Kirschbaum, B.; Loffler, M. Functional expression of a fragment of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase by means of the baculovirus expression vector system, and kinetic investigation of the purified recombinant enzyme. Eur. J. Biochem. FEBS 1996, 240, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löffler, M.; Jöckel, J.; Schuster, G.; Becker, C. Dihydroorotat-ubiquinone oxidoreductase links mitochondria in the biosynthesis of pyrimidine nucleotides. Mol. Cell Biochem. 1997, 174, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawls, J.; Knecht, W.; Diekert, K.; Lill, R.; Loffler, M. Requirements for the mitochondrial import and localization of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Eur. J. Biochem. FEBS 2000, 267, 2079–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukalova, S.; Hubackova, S.; Milosevic, M.; Ezrova, Z.; Neuzil, J.; Rohlena, J. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase in oxidative phosphorylation and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walse, B.; Dufe, V.T.; Svensson, B.; Fritzson, I.; Dahlberg, L.; Khairoullina, A.; Wellmar, U.; Al-Karadaghi, S. The structures of human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase with and without inhibitor reveal conformational flexibility in the inhibitor and substrate binding sites. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 8929–8936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sykes, D.B.; Kfoury, Y.S.; Mercier, F.E.; Wawer, M.J.; Law, J.M.; Haynes, M.K.; Lewis, T.A.; Schajnovitz, A.; Jain, E.; Lee, D.; et al. Inhibition of Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase Overcomes Differentiation Blockade in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cell 2016, 167, 171–186.e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.J. Re-evaluation of Brequinar sodium, a dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitor. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2019, 37, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.J. Antipyrimidine effects of five different pyrimidine de novo synthesis inhibitors in three head and neck cancer cell lines. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2018, 37, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, S.; Merz, C.; Evans, L.; Gradl, S.; Seidel, H.; Friberg, A.; Eheim, A.; Lejeune, P.; Brzezinka, K.; Zimmermann, K.; et al. The novel dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) inhibitor BAY 2402234 triggers differentiation and is effective in the treatment of myeloid malignancies. Leukemia 2019, 33, 2403–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidano, V.; Houshmand, M.; Vitale, N.; Carrà, G.; Morotti, A.; Tenace, V.; Rapelli, S.; Sainas, S.; Pippione, A.C.; Giorgis, M.; et al. The Synergism between DHODH Inhibitors and Dipyridamole Leads to Metabolic Lethality in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers 2021, 13, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainger, J.; Bengani, H.; Campbell, L.; Anderson, E.; Sokhi, K.; Lam, W.; Riess, A.; Ansari, M.; Smithson, S.; Lees, M.; et al. Miller (Genee-Wiedemann) syndrome represents a clinically and biochemically distinct subgroup of postaxial acrofacial dysostosis associated with partial deficiency of DHODH. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 3969–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.B.; Buckingham, K.J.; Lee, C.; Bigham, A.W.; Tabor, H.K.; Dent, K.M.; Huff, C.D.; Shannon, P.T.; Jabs, E.W.; Nickerson, D.A.; et al. Exome sequencing identifies the cause of a mendelian disorder. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, G.; Yan, Y.; Lee, H.; Koppula, P.; Wu, S.; Zhuang, L.; Fang, B.; et al. DHODH-mediated ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer. Nature 2021, 593, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.; Chiramel, A.I.; Schmidt, M.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Whitt, N.; Watt, A.; Dunham, E.C.; Shifflett, K.; Traeger, S.; Leske, A.; et al. A genome-wide siRNA screen identifies a druggable host pathway essential for the Ebola virus life cycle. Genome Med. 2018, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthra, P.; Naidoo, J.; Pietzsch, C.A.; De, S.; Khadka, S.; Anantpadma, M.; Williams, C.G.; Edwards, M.R.; Davey, R.A.; Bukreyev, A.; et al. Inhibiting pyrimidine biosynthesis impairs Ebola virus replication through depletion of nucleoside pools and activation of innate immune responses. Antivir. Res. 2018, 158, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N.N.; Lai, K.K.; Dai, J.; Kok, K.H.; Chen, H.; Chan, K.H.; Yuen, K.Y.; Kao, R.Y.T. Broad-spectrum inhibition of common respiratory RNA viruses by a pyrimidine synthesis inhibitor with involvement of the host antiviral response. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cao, L.; Gao, H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, F.; Lan, T.; Lou, Z.; Rao, Y. Discovery, Optimization, and Target Identification of Novel Potent Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 4056–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luban, J.; Sattler, R.A.; Mühlberger, E.; Graci, J.D.; Cao, L.; Weetall, M.; Trotta, C.; Colacino, J.M.; Bavari, S.; Strambio-De-Castillia, C.; et al. The DHODH inhibitor PTC299 arrests SARS-CoV-2 replication and suppresses induction of inflammatory cytokines. Virus Res. 2021, 292, 198246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]